Van Gogh and Japan

Japonisme is a concept used to describe the study of Japanese art and its influence on European artists. It was present in several currents, including art nouveau and post-impressionism. But this phenomenon is more closely related to Impressionism, as artists such as Claude Monet and Edgar Degas were inspired by the themes, perspective and composition of Japanese prints.

Objects such as lanterns, screens and lacquerware were popular with the city’s designers. Artists such as Monet, Degas and others collected Japanese prints, to later incorporate the Japonisme into their own artworks.

By the hand of Samuel Bing (1838-1905) a great collector and dealer who possessed a great culture (which led him to become very passionate about Japanese art) this ‘Japonisme’ had arrived in Paris. Bing, born in Hamburg, moved to Paris in 1871, and in 1895, together with his Japanese partner Hayashi Tadamasa, founded the gallery L’Art Nouveau, which was to become one of the great centers of Parisian intellectual life.

He also founded a club where members wore kimonos and ate with chopsticks, known as the Jing-lar. In 1875 Bing himself had travelled to Japan, where he bought numerous prints and other valuable objects which, on his arrival in Paris, he exhibited and sold in his shop. Such was his importance that, on several occasions, he was in charge of selecting the Japanese pieces to be exhibited at the Universal Exhibitions.

Japan opened up to the West when the Edo period came to an end in 1868. Paris was flooded with decorative objects and colorful woodblock prints called ukiyo-e. from Japan. Japanese art and crafts had already been a major attraction at the 1862 World’s Fair in London.

Ukiyo-e paved the way for Japan’s mutual relations with other countries, since it developed in ordinary people an interest in foreign science and culture, while at the same time fostering a yearning for travel through the illustrated books that were traded with the West. The Japanese owe to Ukiyo-e the progressive expansion of international awareness.

Initially, most of the prints that reached the West were the work of contemporary Japanese artists of the 1860s and 1870s. Works created from the direct transfer of the principles of Japanese art to Western art, especially those produced by French artists, are known as Japonaiserie or Japonaiserie.

Despite never having travelled to the East, Van Gogh had a strong fixation and obsession with Japanese art to such an extent that several of his works have been considered almost plagiarisms of Japanese artists.

The letters written by Vincent Van Gogh to his brother Theo are an extremely important historical document, as they contain all the artist’s dreams, needs, defeats and conclusions, and are very useful for understanding his work and the creative and sensitive vision he had of the world. Thanks to this correspondence we know how enthusiastically the painter contemplated and absorbed oriental themes, aesthetics and techniques.

For example, in July 1888, he wrote: “Japanese art is something like the primitives, like the Greeks, like our ancient Dutch, Rembrandt, Hals.” Although the painter was never fortunate enough to travel there, he studied and read about Japanese art, which gave him the ability of making his own image of Japan. He collected and copied prints too.

He had bought his first woodcuts in 1885 while living in Antwerp. He hung the prints on the wall of his studio, seeking inspiration and trying to understand their mysterious appeal. He bought as many as 600 prints during his stay in Paris between 1886 and 1888. They provided him with a great source of inspiration.

The artist was seduced by a culture he knew through others and through conversations with other artists influenced by Japonisme. His fascination would become increasingly intense:

“I envy the Japanese, the extreme cleanliness that they have in everything. It is something that is never boring, and never seems to be done lightly. Their work is as simple as breathing and they make a figure with a few sure strokes, with the same ease, as if it were as easy as buttoning a waistcoat”, he wrote to Théo in September of that year.

This intense relationship was reflected in the works he produced in 1887 and 1890, in which he copied prints by Japanese artists such as Keisai Eisen, or incorporated the style, composition, themes and colors of Japanese engravings in works such as Portrait of Père Tanguy (1887).

Experts say that Van Gogh developed a Japanese eye through constant study and reproduction of illustrations of geisha, kimonos and fans; “Their work is as simple as breathing, and they can make a figure as if they were buttoning their waistcoat,” Van Gogh wrote to his brother.

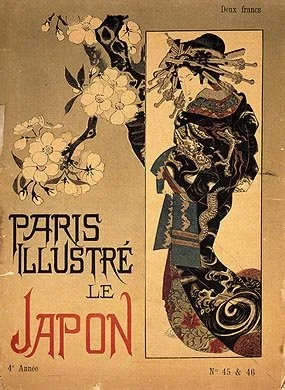

Van Gogh read the first issue of the magazine Paris Illustré of 1886, subtitled Le Japon, which describes Japan very clearly, in terms very similar to those used by the Goncourt brothers, as a land whose sun shone brightly and was hot. Because of this, Japan’s climate was constantly compared to southern Europe, mainly the regions in and around Italy. This is why this talk of the south (the Midi), which Vincent constantly mentions in his letters, led him to move to a place where the light was very similar to Japan, and that this was where artists had to go in order to understand what the Japanese painted in their works.

During his stay in Paris, both Vincent and his brother Theo organized several exhibitions of Japanese prints with the works they had acquired, one of the most characteristic of which was held in 1887 at the café Le Tambourin in Montmartre, and another at the restaurant Du Chatelet in the same year. This fact is reflected in ‘Agostina Segatori’ at Le Tambourin’ in 1887, where, behind Agostina herself, there are depictions of Japanese prints.

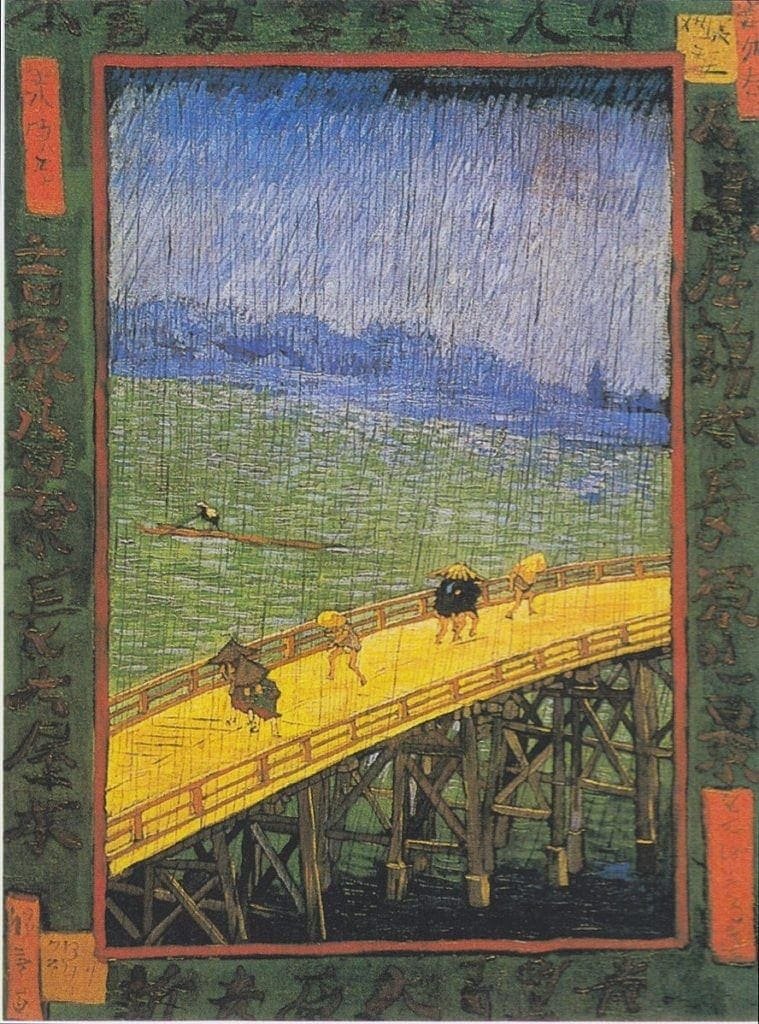

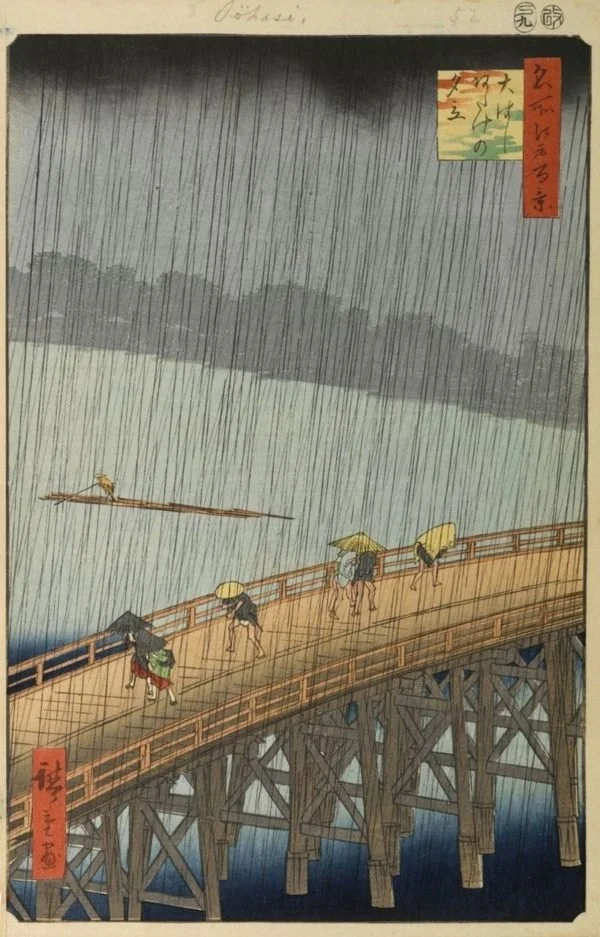

Bridge in the Rain is a painted copy of a woodcut by the Japanese artist Utagawa Hiroshige, but at the same time it is a work with a style of its own. In it, Van Gogh intensifies the tones of color and line, giving the work greater texture. The use of various shades of blue, yellow and green, colors that Van Gogh used constantly throughout his life, give the painting a dreamlike atmosphere, idealized by the number of books and magazines he had read. As a tribute to the Japanese artist, Van Gogh placed a series of kanji or meaningless characters around the painting.

As he did with Bridge in the Rain, Van Gogh produced Flowering Plum Tree (after Hiroshige) based on Utagawa Hiroshige’s Plum Park in Kameido of 1857, during the same year. Similarly, the use of intense colors, the use of line and the decorative kanji round the frame are all noteworthy.

Inspired by the cover of the May 1886 issue of the magazine Paris Illustré, Vincent produced The Courtesan in 1887 based on a reproduction of Keisai Eisen’s Oirán. The original piece is different from the one created by Van Gogh, or the one reproduced on the cover of Paris Illustré, because the print had been reversed.

After two years in Paris, Van Gogh left the bustle of the capital behind him in February 1888. He left for Arles, in the south of France, where he hoped to find the spiritual peace he needed and “the clarity of atmosphere and the color effects” of the oriental prints. He wrote to his friend Gauguin, who was also very enthusiastic about the Japanese examples, that he had looked out of the train window to see if it was still like Japan. Like Gauguin, Van Gogh was convinced that artists needed to be in more “primitive” places, in order to search for vibrant colors. With this in mind, he decided to leave to Arles.

Also, large blossoming branches with a blue sky as a background were one of Van Gogh’s favorite subjects. Almond trees blossom in early spring, making them a symbol of new life. Van Gogh borrowed the subject, the bold contours and the position of the tree in the picture plane from the Japanese print, creating a dynamic composition, with the branches intertwined (Van Gogh Museum, n.d., Almond Blossom).

The Japanese flowering tree provided Van Gogh with a personal symbol that brought him into contact with the vitality and sacredness of nature as depicted in Japanese art and reminded him of his own Dutch tradition’s sense of nature as a religious phenomenon.

Although Van Gogh described his feelings as envy, art historians speak of the link between Van Gogh and Japanese art in terms of inspiration and admiration. Today the passion is reciprocal, as the Japanese public is a loyal admirer of his works.