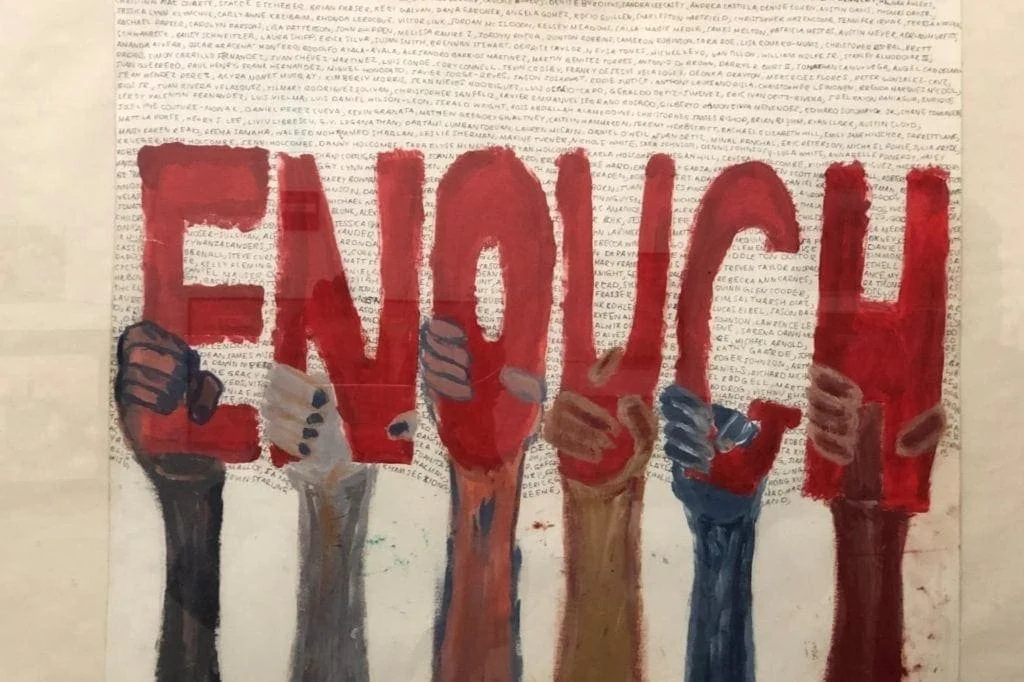

Art Activism

In the ever changing social and political landscape, art remains the constant. Art has always been a way of responding to one’s surroundings, which has often led to societal critique and commentary. This is because ultimately, art reflects life. We all know someone who says “I’m not political,” it’s a phrase one hears often, but it’s a rare truth. There are very few people who do not express themselves through some form of creativity. We all have at least once tried our hands in the kitchen, gone out dancing on the weekends (pre-corona of course), posted a photograph on social media, hummed a tune on our way to work, or even written a love letter. While most of us associate politics with law, government officials and even celebrity status, what we don’t realise is that the creativity we already express is a form of political speech. Infact, one might argue that each and every one of us is actively shaping the political landscape and we just don’t realise it.

The artist has a very special role in the political realm of society. Art’s ability to appear in unexpected situations is a benefit in societies where protest is commonplace. The Center for Artistic Activism puts it best; “traditional forms of protest, like marches, need to constantly increase in size or scope, or descend into violence, to become noticed (and newsworthy), the creative innovation at the heart of artistic activism provides something uncommon, or out of place, that can attract attention and become memorable.”

Historical roots of Activism in Art

Historical roots of Activism in Art

In the 1940’s, Albert Camus wrote, “The doubt felt by the artists who preceded us concerned their own talent. The doubt felt by artists of today concerns the necessity of their art, and hence their very existence.” Over half a century later, his words still remain true. Around the time of this quote, the Great Depression had hit the United States. This was the first time in history that art activism had started to become mainstream in American society. Artists were acting in solidarity with the working class, organzing exhibitions on social and political themes such as poverty, lack of affordable housing, anti-lynching, anti-fascism, and workers’ strikes.

To the present day, art is a fundamental defining aspect of global cultures. It responds to issues and keeps movements alive. Or as Paul Boden says, “It moves with the struggles and moves the struggles forward.” Scottish artist Richard Demarco reminds us, “You’ve got to see that you’re a very useful person as an artist, because your insights and your gifts are such that, as Joseph Beuys says ‘If properly used, you’re the person who can bring healing and regeneration to Society.”

What About Art for Art’s Sake?

So this all sounds well and good, but what about the people who look at a piece of art and see nothing other than what it is, which in some cases, can be a banana duct taped to a wall? If we all view art as just art, it diminishes the potential for inciting change. Art for art’s sake, compartmentalizes art and removes it from most people’s everyday experiences. “In a bourgeois society art like everything else becomes a commodity. It loses its social nature as a free expression of collective experience,” writes muralist John Pitnam Weber. John goes on to critique museums and galleries, for offering culture as a “spectacle divorced from life,” describing this form of art viewing as detached from the everyday experience.

The problem we see here is that removing art from the everyday experience allows artists to ignore larger society, to the point where their individual experience is alienated from it. This can also be said in the reverse, everyone else is perfectly able to ignore art.

Art to Integrate, Not Divide

Sticking a gallery in a low income neighbourhood can be seen at first glance as an attempt to make art accessible. What quickly follows is the contrary, and what seems like a buzz word in all western cities: gentrification. Therefore, one can’t argue about the activist nature of art without acknowledging art’s famous ability to create further social divide. If we are going to use art as a way of facilitating inclusion, a lot of barriers constructed by the art world will need to be kicked down.

Even with the best intentions, artists and activists can be paternalistic toward those whom they are trying to help out. Which can be often portrayed as the artist being the “expert” whose creativity and know-how is being bestowed upon “disadvantaged” people. Artistic activism changes this tune, where the relationship can actually be reversed. It is what the people have to say that is valuable. While culture is something we all possess, we don’t all have the same culture. The foundations of culture (the symbols and stories that give artistic activism its content and form) are different depending on where you are and who you are speaking to. So when it comes to local culture, it is the locals who are the experts.

Gablik believes that art will redefine itself, “In the past, we have had much of the idea of art as a mirror (reflecting the times); we have had art as a hammer (social protest); we have had art as furniture (to hang on the walls); and we have had art as a search for the self. There is another kind of art, which speaks to the power of connectedness and establishes bonds, art that calls us into relationship.”

Where Does One Find Art Activism?

“Activist art exists in many different guises,” writes Kim Berman, “from public art

(murals, performance interventions) to community-based projects, for example. Whatever

forms they take, all share the belief that art does not belong to an economic elite, but is a

communal resource where the line between creators and viewers is often blurred.”

The Democratisation of Art is gaining popularity in the art world, but this concept has been around since at least the French Revolution. It essentially signifies an effort to make art more accessible to all, something that is vital if art is going to “struggle with society and move struggle along” as we previously mentioned.

Gablik predicts that “what we will be seeing over the next few decades is art that is essentially social and purposeful, art that rejects the myth of neutrality and autonomy.” She predicts a new aesthetic model of “art moved by empathic attunement, not tied to an art historical logic but orienting us to the cycles of life;” an art that “helps us to recognize that we are part of an interconnected web that ultimately we cannot dominate. Such art begins to offer a completely different way of looking at the world.”

This shift in aesthetic combined with the democratisation of art, can result in a massive movement in our collective consciousness. This can even be seen today through the rise of social media, where the line between artist and consumer is the thinnest it’s ever been.

Activism is not a Fight

The problem with the way most activism is approached is that people want to view it

as a fight. Emily Wilcox puts it beautifully:

“A basic rule of the universe is that whatever you give your attention to will expand. When you focus on what you are against, that’s where you are putting your attention, and not only do you make your opponent bigger by giving it energy, but you also become that same thing. This is why straight-edge kids who hate drug users eventually become drug users, and second-wave feminists become hierarchical and sexist, and proclaimed anti-fascists talk as though their opinion is the only right opinion. Instead, focus on what you stand for. This can be a lot more challenging because sometimes it means you have to consider options outside of the things you have known. It requires you to use your imagination to envision what you want, and it requires you to trust your creativity in order to follow through with your vision. Basically, you have to think like an artist, as though society were your medium.”

Going back to the wise words of Camus, “The aim of art, on the contrary [to judgement], is not to legislate or to reign supreme, but rather to understand first of all.” Achieving understanding, or at the very least the willingness to understand, is a great help when attempting to attain balance in any situation. I don’t know if I can speak for everyone but most of us are actively seeking balance between one another and with our environment. However, at the moment we all operate in unbalanced hierarchies and authoritarian conventions (men above women; white supremacy/privilege; humans above nature, and so on). In order to overcome this, we all need to develop an understanding of “the other” – not only in political movements, but in our own communities and daily lives. Art can be a great facilitator of this.

Art as a way of cultivating empathy

If we all want to live in an equal society, and actually feel responsible to not exploit others, it is necessary for us all to achieve a sense of compassion, which is mostly rooted in empathy. We all have the basic capacity for empathy, but it is our cultural environment that either encourages or suppresses our emotional response to things. We are all more influenced by our environments than we realise, what if the art around us had the ability to spark our inner sense of compassion?

Telling someone to care about a social issue doesn’t really change their mind at the end of the day. That’s why straight fact won’t work, people can’t feel that, as they do a piece of art. Think of a fight with someone who’s hurt you emotionally or physically. If you state plainly to their face that they have hurt you, they won’t necessarily believe you. If you cry or show physical emotion, that usually warrants an actual reaction based on their empathy for you in that moment. A powerful artwork always contains a surplus of meaning: something we can’t quite describe or put our finger on, but moves us nonetheless. Its goal, if we can even use that word, is to stimulate a feeling, move us emotionally, or alter our perception.

On the other hand, executing creative projects can help one to release mental and emotional blockages in a productive and nonviolent way; it enables one to practice critical thinking, see abstract relationships, and develop resourcefulness. That being said, art as a form of activism both allows for the activist to successfully get their point across while making people feel the message in their gut.

Collectively, we all are constantly redefining our culture, whether we notice it or not. Both the artist and the consumer of activist art are consciously choosing to have their part in redefining society as we know it.